The world first knew about Tafadzwa Z. Taruvinga from his memoir, ‘The Educated Waiter: Memoir of an African Immigrant’. In it, Taruvinga details how he felt the land of his birth, Zimbabwe, for Rhodes University (South Africa) where he enrolled for his bachelor’s in economics and management. The economy back home did not do him any favour and he struggled to pay his fees and even to keep food on his table some days. At one point he even dropped out of school to work so he could raise enough money for his tuition.

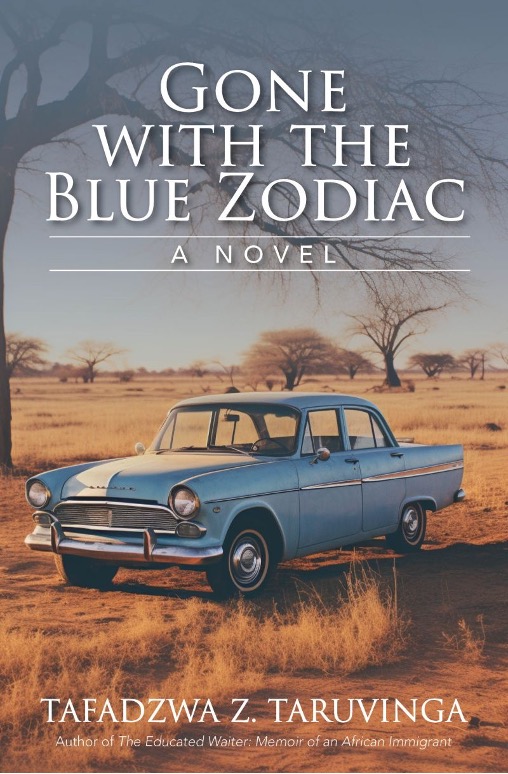

Today he is the holder of two degrees, his bachelors in economics and management (Rhodes University) and a Master of Art in Creative Writing (University of the Witwatersrand). He lives in Johannesburg and works at the Archbishop Desmond Tutu Leadership Foundation. His project from his Masters thesis is his debut novel, ‘Gone With the Blue Zodiac’. We caught up with Taruvinga to talk about all things books and creativity.

The Exclusive * KM – Kudzai Mhangwa, TT – Tafadzwa Taruvinga

KM: Thank you for agreeing to this interview, I’m so excited. Tell us who Tafadzwa Taruvinga is in your own words.

TT: Talking about books and the important stories that they carry is always exciting for me too, so thank you, My Afrika Mag, for creating this interview opportunity. I believe I’m a contributor, through creative writing, to the very important task of changing the negative historical narrative that has been and continues to be told about the African continent. Many Africans are using their talents and various devices to do the same – and, thanks to technology, we can now do so better than others could six decades ago – but we still have a long way to go. I’m passionate about fostering thought leadership on the African continent through academic research, writing and literature.

KM: We got introduced to you from your book ‘The Educated Waiter: Memoir of an African Immigrant’. How did this come to be?

TT: This book is not my first because I have experimented with my writing to publish books such as ‘Serve Your Customers Excellently, Or Not At All!’ with which, at the time, I intended to persuade top managers in Zimbabwe to streamline customer service across sectors. But it’s fair to say that ‘The Educated Waiter: Memoir of an African Immigrant’ and ‘Gone With The Blue Zodiac’ are more visible in the public domain. I often describe ‘The Educated Waiter’ as my outpouring. My story inadvertently addresses issues like education and my struggles as a student, poverty, classism, racism, immigration and xenophobia, which, like many Africans looking for better lives in a complex world, I have experienced. Writing this memoir made me my own therapist.

KM: What was your experience with getting published?

TT: African writers struggle to get published and I was no exception, although I was also fortunate. In 2017, Jacana Media in Johannesburg invited applications for an initiative called ‘Pitch to Publication’. I applied for it and was shortlisted. There, aspiring authors were asked to present their book ideas to a panel of selectors. I didn’t make it to the final round, but the panellists liked my concept of Tafadzwa the protagonist who had gone to Rhodes University but was a waiter. I started writing the story centring on this character. By 2018, I had written so much that when I, at a book launch, I met Melinda Ferguson – who was the founding publisher of MF Books (which was an imprint of Jacana Media) – I convinced her to publish my work. The book was published in 2019, then I bought the publishing rights from MF Books in 2020 to fully own the work.

KM: What was it like baring your personal life in such a way and also immortalising it in a book so generations could read it?

TT: Difficult at first, then I later realised that I couldn’t authentically write my story without sharing intricate aspects of my life. Ironically, that’s where the self-therapy lay because I could suddenly relinquish things that had tormented me for a long time, such as growing up without my father who passed on when I was seven. Now I think perfection and completion are less important than embracing my journey. That kind of epiphany is refining. I’ll give you an example. I studied at Rhodes University with classmates whose fathers were alive – and wealthy.

Eleven years later in 2016, while working as a waiter in the heart of Sandton, I remember wishing no one that I knew from my student days would ever see me working as a waiter. Then it happened one day, and, embarrassed, I wept when I got home. After that day, something magical and irreversible happened. It no longer mattered what anyone else thought of me. Self-awareness and leveraging opportunities – big or small – mattered more. So, I started sharing my story with restaurant patrons, some of whom turned out to be executives who set up job interviews for me. I now know believing in myself and having a vision are more substantial than aesthetics.

KM: How was the reception. Was the book on a mission and if yes, was it accomplished?

TT: Based on several reviews that are available online, coupled with the feedback I receive when I socialise, ‘The Educated Waiter’ has been well-received in Zimbabwe, South Africa and within the wider African diaspora. I wrote the book to capture issues that were personal, intertwined with events that were taking place at different times, as well as issues that were or are close to my heart, like intracontinental migration, integration and exclusion. Some people who have read the book say they can relate to many aspects of my experiences in different ways. And that, I suppose, is what makes the mission – however that mission is imagined – accomplished.

KM: Now you have this new book out ‘Gone With The Blue Zodiac’. Tell us a bit about it.

TT: ‘Gone With The Blue Zodiac’ is a fictional story that is inspired by my father’s death in 1990 when his car collided with a train in Harare’s south-western industrial area. That is the story’s premise, but I then develop the character Nyika Denga who is married to Bettina, and they have two children – Tungamirai and Paidamoyo – as well as the family dog, Mazowe. Like my father’s, Nyika’s car collides with a train on a stormy night in 1993 and he dies in the accident. I create, perhaps in my attempt – some thirty-three years later – to reimagine my father’s final moments, the critical scene of Nyika’s death from the point of view of a locomotive operator who I name Engineer Martin Rukukwe.

This story, told from multiple perspectives, is about the encounter that Nyika’s family, and other characters that I introduce as the story develops, has with grief, and how grief forces them to face their inner contradictions. Andrew Chatora, a scholar and writer who teaches English in the United Kingdom, asserts, in his recent review of ‘Gone With The Blue Zodiac’, that the story partly evokes the 1993 film ‘Neria’. I agree with Chatora, but the story is far from sombre, and it intersects with other scintillating themes such as romance, infidelity and sex, culture, language and Zimbabwe’s history between the 1970s and the early 2000s. The story is set in rural and urban Zimbabwe and, therefore, nuanced and undulating.

KM: I read it and I must say it “felt like home”. The use of Shona proverbs and the atmosphere felt Zimbabwean. Did you find it easy to write this?

TT: I’m extremely passionate about speaking, writing and reading chiShona as much as I do English, and creating equality between chiShona and English. While I think writing English narratives is important and interesting, I want to play a part in preserving the chiShona language, even in the context of English narratives. My consternation comes from how the movement of Zimbabweans to other parts of the world seems to be causing the dissipation of chiShona. I’ve committed to using creative writing to preserve chiShona in a way that is contemporary and memorable.

‘Gone With The Blue Zodiac’ is part of my creative project for the Master of Arts in Creative Writing degree, for which I graduated at the University of the Witwatersrand with a Distinction last year. When I submitted my project proposal to my supervisor in 2020, I expressed my intention to infuse about 10% of chiShona words and phrases in an English narrative as a form of literary experimentation. She was fascinated but also worried whether a non-chiShona-speaking reader would, therefore, understand the story. In turn, I ensured that any reader could either understand or infer the meaning of every chiShona inclusion, but I didn’t explicitly define these words or phrases.

KM: While reading it I felt almost tugged between the different generations (Mai Huku, Bettina and Tunga). Was this a point you had set out to make while writing this book?

TT: Social norms, languages and cultures in rural and urban Zimbabwe, like in any other country, continuously mutate into some kind of existential kaleidoscope. They are inevitably influenced by both dogma and popular culture, so you can expect in the story characters like Mai Huku, who are rooted in a “whatever was before shall remain so” manner of thinking. This is reflected in her rhetoric and behaviour. Tunga was relatively easy for me to create because he is a teenager at approximately the time when I was one in the 1990s, and therefore, an extension, and even an exaggeration, of myself. I didn’t struggle to remember and modify his thought processes, mannerisms and language. Bettina was a more complex character to develop because she was hardly visible in Zimbabwe’s 1990s: a woman who could be significantly unorthodox and either subtly or overtly assert her alternative existence. Overall, each character gave me an opportunity to experiment.

KM: You also made use of Shonglish in the text. Why this choice?

TT: Shonglish, which is a language formed by combining Shona (or chiShona) and English, accentuates minutiae in a way that English sometimes couldn’t. Take a word like ‘roorad’, which I have created and used in ‘Gone With The Blue Zodiac’, for example. The chiShona verb is kuroora, which means to pay a bride price (roora being the noun) to a woman’s family as a form of customary marriage. Therefore, roorad could be applied as a past tense verb: “He roorad her,” one could say.

In context, roorad would be more definitive than a purely English description of the same act, especially if a scene is set elaborately and exposition is used to show the drama that typically occurs at roora events in the context of Shona or other African protocols. By the time such an event is solemnised and completed, and a woman is then described as one who has been ‘roorwad’ (an adjective derivative which describes the state of ‘the one for whom roora has been paid’), a reader will have a palpable sense of the gravity of roora proceedings. In my view, Shonglish, combined with English and chiShona in English texts, is an evocative writing device.

KM: There is even a chapter in which the dog Mazowe narrates. Why give a voice to a pet?

TT: I thought doing so would challenge me in the sense that creating a language that may not be understood by the reader of a dominantly English text also had the potential of throwing them off. Secondly, what would the point of including a dog character be, other than decorative, if he couldn’t speak to us? Most importantly, Mazowe is with Nyika when the accident happens, so it was particularly important for me to then tap into Mazowe’s sensibility in addressing grief. After all, we often hear that dogs are attuned to and share in human emotions. How could we understand this if a dog couldn’t express his thoughts and feelings in his language that is, compared to the language spoken by human beings, limited? That said, creating Mazowe’s language was extremely difficultto create, but worthwhile. I consider Mazowe’s chapter to be the story’s disruptive centrepiece.

KM: The issue of blended families is also prevalent in the book and in today’s society. What’s your view on this issue?

TT: I assume by a ‘blended family’ you mean a relationship within which a divorced man, or a man with children from a previous relationship, marries a woman; or a divorced woman, or a woman with children from a previous relationship marries a man, and they form a new family comprising their respective and additional children. I’m Catholic, and the church, drawing from Mark 10:2-16, teaches that either of the above would constitute adultery. But the nature of matrimony and families in modern society has also changed.

My view is that people should be in relationships or marriages in which they are reasonably happy, are embraced and can become better versions of themselves. I believe in fighting hard for a marriage to work when it’s tested by various factors, but I think, for example, getting divorced is a better alternative to the death of a woman who succumbs to her husband’s pounding. Instead, if they get divorced and each find a better suitor with whom to lead a peaceful and happy life, this, I think, is better. Sam, Edith, Bettina and Sandra in ‘Gone With The Blue Zodiac’ test the concept of blended families in interesting ways.

KM: The women in the book are quite interesting and the decisions they make are quite bold, given their time (Faustina and Bettina). How did you craft these women?

TT: I think bold Black women have always existed but were less visible in Zimbabwe before, when society was relatively more conservative than it now is. In ‘Gone With The Blue Zodiac’, Faustina, Bettina, Sandra and other women push significant boundaries and create new norms earlier than women were thought to. That said, Black women in Zimbabwe have, in the last four decades, initiated changes in societal norms in more ways than have been acknowledged. For example, many women enlisted in the Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army (ZANLA) to fight against Rhodesia’s White minority rule in the 1970s’ Second Chimurenga.

Many Black women took up tertiary education, professional training and artisanry through the Harare and Bulawayo Polytechnics, and other institutions, from the early 1980s, after independence. In 1990, women who wore trousers were heavily frowned on, but that had become a visible trend (and, perhaps, a form of emancipation) by 1995. To sum it up, I exaggerated the different forms of rebellion and changes that women regularised between the 1980s and 2000s, to show that the norms that we now see among Black women in modern Zimbabwe could have started earlier than they are generally documented, if at all.

KM: An interesting quote from your book is, “After all, he (Nyika) is a teacher. He speaks for others to listen.” Do you ever feel like a teacher who often speaks to an audience in a place of ‘authority’?

TT: I consider myself to be both a teacher and a student in different contexts. I can confidently share knowledge on subjects that I have studied and understood, when I access platforms through which I can share knowledge. The opposite is also true. I listen to and learn from those who impart knowledge on subjects that they are experts in or know about. I love how technology has eased our ability to access knowledge, and I see the value of reading as much as I write. You know what? I aspire to be as knowledgeable as Nyika Denga!

KM: What is next for Tafadzwa Taruvinga?

TT: I’ve created 20 sketches of children’s stories in chiShona and English and written two of them. In the coming months, I’ll be designing illustrations that will bring various characters in the two children’s books to life. I’m very excited about this project because it aligns well with my vision of using storytelling to preserve chiShona and some aspects of Shona culture.

There continues to be interest in ‘The Educated Waiter’ and ‘Gone With The Blue Zodiac’, which can be found in Zimbabwe at the House of Books, South Africa at Book Circle Capital (Johannesburg) and Book Lounge (Cape Town). I’m reachable on Facebook) or Instagram (TZ Taruvinga ), and by connecting with me, Tafadzwa Z. Taruvinga, on LinkedIn (Tafadzwa Z. Taruvinga | LinkedIn).

His life story is inspiring been wanting to read, “The educated waiter,” for years where can we find the book?

Thanks for your interest, Chiedza. You can find the book, in paperback, at House of Books in Harare, Book Circle Capital in Johannesburg and Book Lounge in Cape Town.