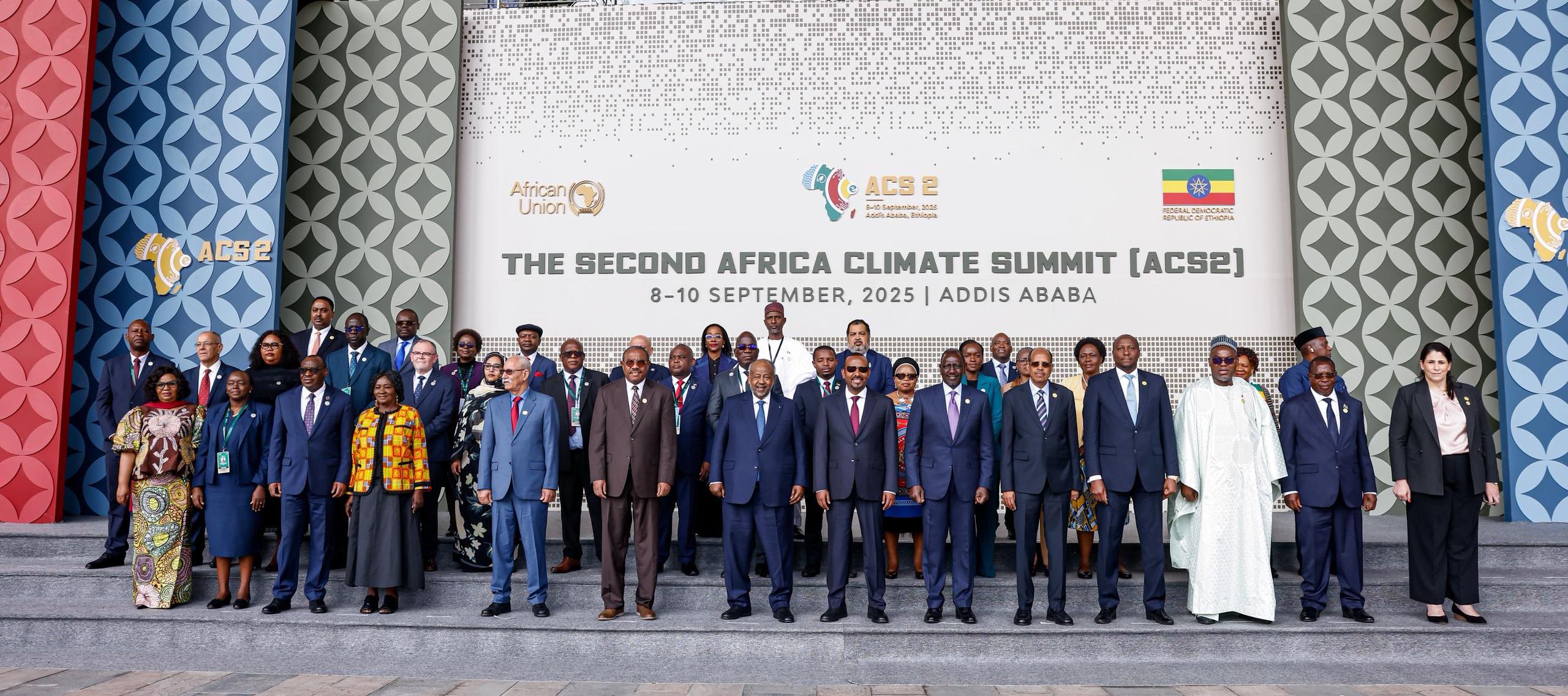

Ethiopia’s capital, Addis Ababa, hosted the Second Africa Climate Summit (ACS2) from 6 to 8 September 2025, positioning the gathering as a pivotal moment in advancing a pan-African climate agenda. The summit followed the inaugural meeting in Nairobi in 2023, which had sought to recast Africa not as a victim of climate change but as an actor central to delivering global solutions (UNFCCC).

On the eve of the summit, Ethiopia’s Minister of Development, Fitsum Assefa, captured the prevailing mood with the declaration: “We are not here to beg. We are here with solutions, with a vision, and with a desire to build a shared future.” This sentiment was echoed throughout the proceedings as governments, institutions and civil society sought to demonstrate that Africa possesses both the resources and ideas necessary to shape climate responses.

While only four African heads of state attended, compared with a dozen in Nairobi, the summit produced significant financial pledges. These included a USD 50 billion annual fund for African climate solutions and USD 100 billion from African financial institutions to drive a green industrial revolution. According to Iskander Erzini Vernoit, director of the Imal Initiative, these commitments illustrate that Africa is “brimming with solutions and efforts to take action”. However, he emphasised that the continent’s call for a fairer global financial architecture remains central, particularly in ensuring that wealthier nations meet obligations enshrined under the Paris Agreement (UNEP).

The Addis Ababa Declaration on Climate Change, adopted on the summit’s final day, reaffirmed that the climate crisis is fundamentally a matter of economic justice. It estimated Africa’s needs at USD 3 trillion by 2030 and demanded that developed nations honour long-standing financial commitments to support Africa’s energy transition and adaptation. The declaration stressed that climate finance from historical polluters is a legal obligation and not charity. Current adaptation finance stands at only USD 14 billion annually, far short of the USD 84 billion required each year (OECD).

The declaration also sought to shift perceptions of Africa from a climate-vulnerable region to a hub of solutions, drawing attention to its vast renewable energy potential and critical mineral reserves. Yet, concerns were raised that the language of the declaration lacked precision and assertiveness. Xolisa Ngwadla, a veteran of the Paris negotiations, observed that stronger representation from African heads of state might have enabled more forthright debate and a clearer articulation of priorities.

The role of external actors also drew attention. Unlike Nairobi in 2023, where the United States and European Union featured prominently, ACS2 saw limited Western presence. The EU’s representation was confined to Teresa Ribera, Executive Vice-President for a Clean, Just and Competitive Transition. Denmark pledged USD 79 million to support agricultural transformation, while Italy reaffirmed its USD 4.2 billion climate fund, committing 70% to Africa.

China’s influence was more visible, reflecting its position as the leading supplier of solar and renewable technologies to the continent. African solar imports surged to 15 gigawatts in the year to June 2025, a 60% increase on the previous year, with the majority sourced from China (IRENA). While this has accelerated access to clean energy, critics warned of the risk of Africa being confined to the role of consumer rather than producer. Brian Kagoro of the Open Society Foundations cautioned that partnerships must not reproduce “histories of role assignment where Africa is constantly a junior partner”.

Civil society voices raised sharper critiques. Mwanahamisi Singano of the Women’s Environment & Development Organization argued that the summit risked becoming a platform dominated by private capital, describing it as “a small COP”. Similarly, Alaka Lugonzo of Global Witness noted the failure to connect climate discussions with broader priorities such as food sovereignty, industrialisation and job creation. These interventions highlighted the ongoing struggle to ensure coherence between climate strategies and wider development imperatives.

In a bid to improve strategic planning and inclusivity, the Addis declaration proposed that the summit should henceforth convene every three years, rotating among Africa’s five regions under the African Union framework. Yet, questions remain as to whether Africa’s unity, tested in Addis, can be sustained in the run-up to COP30 in Belém, Brazil. The declaration provides a foundation, but its impact will depend on whether wealthier nations meet what Africa defines as their legal obligation to provide climate finance.

For Africa, the journey to Belém is not about seeking sympathy but asserting agency. The continent’s future role in global climate governance will rest on its ability to articulate a coherent vision that marries climate justice with economic transformation.